Mood:

Topic: globalWarming

Today's opinion piece by Paul Sheehan (Fairfax Sydney) - who it has to be said has major credibility/ethical problems for urging the Israeli war on Gaza without declaring secret Israeli funding, promoting a shonky bottled water product - has again got it badly wrong today.

The drum beat of misconceived non sequiturs and egotistical posturing by science gumbies marches on.

Here is Professor James Hansen of NASA responding to all the fakes and phonies on 9th Dec 2009 on our ABC Lateline show just prior to Copenhagen debacle. We highlight in bold the section on heat island effect and the NASA sourcing of global temperature metrics:

Transcript

TONY JONES, PRESENTER: Now to our interview. Dr James Hansen heads NASA's Goddard Institute of Space Science. The institute has been publishing global temperature data since 1987 and is now one of the key sources of data for climate scientists.

Hansen's own testimony to the US Congress in 1988 brought world attention to global warming. His latest book Storms of my Grandchildren carries the subtitle, "The truth about the coming climate catastrophe and our last chance to save humanity".

He joins us from New York. Professor James Hansen, thanks for joining us.

JAMES HANSEN, CLIMATE SCIENTIST, NASA: Sure, glad to be with you.

TONY JONES: Now you're accusing governments of lying through their teeth even as they sign up to large emission reduction targets for Copenhagen. Why so pessimistic?

JAMES HANSEN: Well it's very easy to show that they are either lying or kidding themselves because all you have to do is look at the geophysical data. You know, the governments all around the world now agree that we're going to have to stabilise atmospheric composition, carbon dioxide in particular, at a relatively low level.

And if you look at how much carbon there is in oil, gas and coal, what you quickly realise is that oil and gas is already going to be enough to get us up to approximately the dangerous level. The only way we can solve the problem is by phasing out coal emissions and prohibiting unconventional fossil fuels like tar sands and oil shale.

But in fact, if you look at what's happening, the United States just signed an agreement with Canada to make a pipeline to carry oil from tar sands to the United States, and Australia is expanding its port facilities to export more coal.

And coal fired power plants are built all around the world. Oil is even being squeezed out of coal. So there's absolutely no way that the world can meet the kind of targets that they're talking about for future decades. So they're just putting out numbers, you know, goals which absolutely cannot be met.

If you're going to use that coal, then you would have to tell Russia to leave its gas in the ground and tell Saudi Arabia to leave its oil in the ground but nobody's proposing that and you know they wouldn't do it anyhow.

TONY JONES: You've also described the whole Copenhagen approach as fraudulent because of its, quote, "ineffectual cap and trade mechanism". Now why do you say global emissions trading won't work?

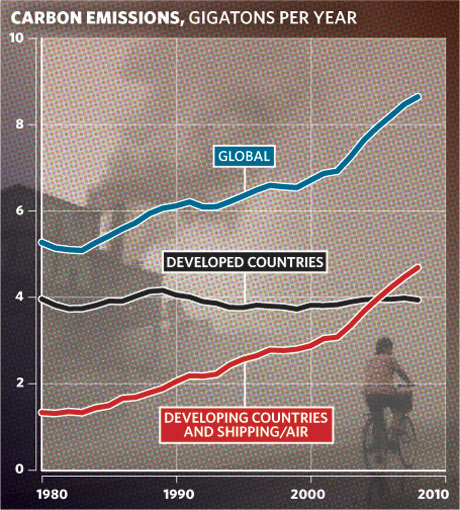

JAMES HANSEN: Well we can prove very easily that cap and trade with offsets is not going to work. We tried that with Kyoto and the global emissions actually accelerated, even the rate of growth increased after the Kyoto Protocol.

A few countries cut their emissions a bit but as long as the price of fossil fuels is the cheapest energy, then they're going to be used by somebody. So this cap in trade and offsets, that's, basically what this is, it's like the indulgences of the Middle Ages, when the Catholic Church would sell forgiveness for sins.

This was great for the bishops, they collected a lot of moolah, and it was great for the sinners, because they got forgiven and they could still go to heaven or at least they thought they could.

That's what's happening in Copenhagen. Developed countries are coming and they're looking for these offsets so they can continue business as usual, they can continue their sinning, but developing countries, well they're happy to go along with that if the developed countries give them some money, you know, for climate adaptation or for the offset mechanisms if that will result in some money going to developing countries.

So that's what's happening. You've got both parties making this kind of a deal, and who's getting the short end of the stick? Our children and grandchildren, because the emissions are not going to decline. In fact, they'll continue to increase. That's as plain as you can see that very easily.

TONY JONES: There's been a huge debate in Australia over emissions trading. Are you saying that even with the best will in the world an emissions trading scheme in Australia will be ineffectual.

JAMES HANSEN: Absolutely. These cap and trade trading schemes are a terrible idea. You can see what they do. They are a way to continue business as usual because they include these offsets, for example. They're not attacking the fundamental problem. Who they're good for is the big banks. In the United States it's going to be Goldman Sachs, and Bank of America, the trading companies.

They have trading groups within their bank who are very skilled and they're going to make money, and where does the money come from? It comes from the public. There will be increased energy prices, big banks will make money, but the problem will not be solved.

There will be little reduction in emissions. Unless you attack the fundamental problem, you cannot solve the problem. And the fundamental issue is that fossil fuels are the cheapest energy. You must put a price on carbon emissions.

And the way to do that, and to make it acceptable to the public and actually very beneficial to the public, is to return the money that's collected from a carbon tax, and that tax needs to be applied at the source, at the mine or the port of entry.

You then distribute that money to the public, so that they will have the money to invest in more efficient vehicles, in insulating their homes, and that would encourage innovations, innovators would develop carbon free or low carbon energy sources.

That's the way that you can drive the system to slowly phase out fossil fuels, but the cap and trade doesn't do that at all, and it's impossible. As long as fossil fuels are the cheapest energy, you're not going to phase them out.

TONY JONES: Now you've proposed what you call a uniform rising price on carbon; effectively a global carbon tax. Now it's a simple approach but it would require carbon tariffs to be levied against those who refuse to put a price on carbon. But isn't that a serious problem? Won't it lead to trade wars?

JAMES HANSEN: No, in fact it is far simpler. As we saw in the Kyoto Protocol, you cannot get all the countries to agree, you have to bribe them one by one to try to get them to sign up to the Kyoto Protocol or a Copenhagen follow up.

But, in the case of a carbon price, which is simple and honest, it's a much easier task. All you need to do is get the major players to agree to put a carbon price on. And then if any countries don't want to do it, well then you put a tariff on the products that you import from those countries that are made with fossil fuels.

In effect, most countries would then decide, well, we would rather have our internal carbon tax because then we get to collect the money rather than the other country. That is much simpler than cap and trade.

TONY JONES: Can we talk about the science of global warming and climate change now, because as we've gotten closer to Copenhagen, the sceptics have become much louder. There's been a fierce backlash against the science. What do you think is going on here?

JAMES HANSEN: Well, the science, as you know, has become very clear. The evidence for climate change around the world is widespread. The Arctic Sea ice melting, glaciers receding all around the world, climate zones are shifting, the subtropics are expanding, and that's affecting Australia, by the way, as well as the south-west United States and the Mediterranean region, and that's a reason why we have more extremes, including heatwaves and fires.

But also, when we have rain, it is heavier, because warmer atmosphere holds more water vapour. We see the climate change all over the planet, there's no question about that.

TONY JONES: But why do you think there's been a revival of scepticism against the science? You must have been disturbed yourself recently by the leaked email exchanges between your fellow scientists at Britain's climate research unit.

Now sceptics are using these emails to support their case that scientists are trying to hoodwink us, that scientists are falsifying data or hiding away evidence that disproves their arguments.

JAMES HANSEN: Yeah, these are very desperate efforts by the contrarians and those who are supporting the business community that wants to continue business as usual. But, you know, the data that is used to determine the temperature change over the last century or so, that data is available to everybody.

If there was anything wrong with the analyses that showed the magnitude of this warming, don't you think that these contrarians would quickly show, do their own analysis and show that there really wasn't any warming? Of course not because they know very well.

You know, they've tried to examine or data and they did find one flaw, which turned out to be 3/100ths of a degree and was an easily explained mistake, but that's the kind of thing, they're looking for nitpicking. They try to find small things and then they question the integrity of the scientists.

But in fact, there's the evidence for climate change, and the analyses is very strong. It's true that in some of these email exchanges that some of the scientists did some things which I think they probably regret.

For example, we should always make our input data available to the community, to anybody, so that they can check our analysis. But, in fact, we've been doing that for many years, and as I say, nobody can find anything that disproves proves our analysis.

TONY JONES: Okay well one of the published emails we're talking about goes to the key part of the sceptics argument that since 1998, the hottest year on record, carbon dioxide in the atmosphere kept going up, but the temperature didn't keep going up with it.

Now you've been bombarded, I understand, with scores of messages along those lines from people who want you to repent and admit that global warming is a hoax. So how do you respond to them?

JAMES HANSEN: You know, if you look at this global temperature curve and smooth it over a few years you'll see that it's continued to increase over the last decade. And in fact, it's not true that 1998 was the warmest year. 2005 was the warmest year.

The British analysis shows 1998 as the warmest year because they exclude polar regions, because there are no weather stations there or very few. But there are other ways to estimate the temperature in the polar regions and in fact, because of the decreased sea ice in the Arctic it has been warmer and warmer in the Arctic.

And when you include these polar regions, it turns out that 2005 was the warmest year. And when you average over a few years you'll find that the temperature curve has continued up. And besides, you don't expect the temperature to go up every year.

There's a lot of natural variability in the system primarily due to the tropical El Nino/La Nina cycle. And now we are moving into the El Nino phase, so it's a pretty good bet that, first of all, this year is going to be one of the warmest years, 2009, and 2010 will probably be the warmest year on the record.

TONY JONES: Is there already evidence for that? I mean are you seeing early data from your global temperature recordings?

JAMES HANSEN: Yeah, we see the data up to now, and we know that the global temperature tends to lag a few months behind the tropical temperature. So it's because the El Nino started a few months ago, it's likely to have its greatest effect on 2010, but it's already having an effect this year making this year some place between the second and the fifth warmest, it depends on the November and December data, which we don't have yet.

TONY JONES: Okay, can you tell us how the Goddard Institute takes and adjusts these global temperatures because sceptics claim that urban heat centres make a huge difference; that they distort global temperatures and they make it appear hotter that it really is.

So do you adjust, in your figures, for the urban heat zone effects?

JAMES HANSEN: We get data from three different sources and we now, in order to avoid criticisms from contrarians, we no longer make an adjustment. Even if we see there are eight stations in Alaska and seven of them have temperatures in the minus 30s and one of them says plus 35, which pretty obvious what happens, someone didn't put the minus sign there, we just, we don't correct that.

Instead we send an email or letter or a letter to the organisation that produces the data and say, you'd better check the Alaska temperatures, because we don't want to be blamed for changing anything. But as far as adjusting for urban effects, we have a very simple procedure.

We exclude urban locations, use rural locations to establish a trend, and that does eliminate - though urban stations do have more warming than the rural stations, and so we eliminate that effect simply by eliminating those stations, but it's very clear that the warming that we see is not urban, it's largest in Siberia, and in the Arctic and the Antarctic, and there aren't any cities there, and there's warming over the oceans, there are no cities there. So it's not urban warming that's just nonsense.

TONY JONES: Well if I understand you correctly your biggest fear now is that these built in temperature rises will trigger what you call feedback mechanisms. Can you explaining how they work, and what are the implications of them?

JAMES HANSEN: Yeah, well that's what makes climate a really dangerous situation, because of the inertia of the system. It takes the ocean a long time to warm up, it's four kilometres deep, and it takes icesheets a long time to get started to move, they're very thick and have a lot of inertia.

The problem is that as these changes begin to occur, and they are beginning to occur - Greenland is losing ice faster and faster and Antarctica is beginning to lose ice at a rate of about 150 cubic kilometres per year - as you get to a certain point, you can get to a point where the dynamics of the system begins to take over.

If the icesheets begin to collapse, by that time it's too late. You've passed the tipping point and the icesheet is going to end up in the ocean. So, that's one of the tipping points. Another one is methane hydrates. We're beginning to see methane bubble out of the tundra as it's melting.

There's a lot more methane hydrates on continental shelves. As the ocean warms that methane hydrate can also begin to release methane, which is a very strong greenhouse gas and can cause amplifying feedback which makes the global warming much larger.

And this is not idle speculation, because we can look at the history of the earth. And in past global warming events we have seen those kind of amplifying feedbacks which then make the change extremely large.

TONY JONES: Okay, well you're talking about what you find from the examination of ice core data. Is there a comparable period in history, the history of the planet that is, where warming accelerates due to these feedback mechanisms, and do you get much more rapid sea level rises during that period?

JAMES HANSEN: Yeah, well, in the relatively recent paleoclimate, coming from the last ice age to the present interglacial period that we've been living in for 10,000 years, when that icesheet, the big icesheet on North America began to disintegrate, sea level went up five metres per century. That's one meter every 20 years for several centuries. So once an icesheet begins to melt and begins to disintegrate, things can move very rapidly.

TONY JONES: Okay let's go quickly through a couple of the other key arguments put forward by the sceptics. Why worry about carbon dioxide when water vapour is a stronger greenhouse gas and actually occurs naturally?

JAMES HANSEN: Yeah, that's the screwiest argument which keeps being made again and again and again. The amount of water vapour in the atmosphere is determined by the atmosphere's temperature, everyone should know that. Look at the difference between winter and summer.

As you go to a warmer climate the atmosphere holds more water vapour because at the places where the humidity reaches 100 per cent the water vapour falls out as water or snow. And therefore, as the planet becomes warmer, the atmosphere holds more water vapour.

That's why we get heavier rain falls as the planet gets warmer. So this water vapour is an amplifying feedback. It makes the greenhouse effect much stronger. But it's not something that just changes on its own accord; it changes in response to the temperature changes.

TONY JONES: Okay, if I understand it correctly your argument is that climate change is not only about droughts, but that effect you're talking about will cause much more frequent and much more severe storms; is that correct?

JAMES HANSEN: Yeah, the, both extremes of the hydrologic cycle must increase, become more intense as the planet becomes warmer. At the times and places where it's dry, the increased heating of the surface makes it hotter and drier.

On the other hand, the oceans, the places where you have water, the increased heating evaporates more water, so the atmosphere holds more water vapour and at the times when you get rainfall you will get heavier rainfall and greater floods, so the extremes of the climate increase, the extremes of the hydrologic cycle.

Now as far as storms are concerned, the storms that are driven by latent heat - that means thunderstorms, tornados, tropical storms - the strongest ones will get stronger because there's more fuel. The water vapour provides the fuel for those types of storms.

Not all of them will be stronger, but the strongest ones will be stronger than the strongest ones now. But in addition to that, and one thing I talk about in my book, Storms of my Grandchildren, I'm talking about the mid-latitude storms, the fact that as the icesheets on Greenland and Antarctica begin to melt more rapidly than they are now, they will discharge ice fast enough that it will cool the surface of the ocean, nearby ocean, in the North Atlantic and in the circum Antarctic Ocean.

That will cause the temperature gradient between low latitudes and high latitudes to increase, so the storms that are driven by horizontal temperature gradients will become stronger, and these can be very damaging storms, this is like the storms that hit the Netherlands and England in the 1950.

They can do enormous damage. So, yes, it's true that all the storms that we can think of will become stronger as the climate becomes warmer.

TONY JONES: James Hansen, one final question: what's your estimate; how long do we have before the planet reaches one of those tipping points that you're talking about and global warming is irreversible? And if that happens, what are the consequences?

JAMES HANSEN: Well, you know, we are probably, we're already into the dangerous level of carbon dioxide and it's going to increase more. If we would phase out the coal emissions over the next 20 years, then CO2 would peak at something like 425ppm.

Doesn't look like we're starting to phase out coal though, so it may go higher than that. We're going to go well into the dangerous zone, and some things are going to happen out of our control. But that doesn't mean we should give up, because whether we get a sea level rise of one metre, or 25 metres makes a huge difference.

What we will need to do once people really see what's happening, is we're going to need to restore the planet's energy balance, or make it negative, and you do that by reducing the amount of these greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, and so the planet begins to cool off a bit.

And then, even though we're going to get some icesheet disintegration anyhow and we're going to lose some species because we're already pushing some of them, we're putting a lot of stress on many species, but we don't, that doesn't mean we should give up and decide we're willing to give up all of them.

TONY JONES: James Hansen, we're going to have to leave it there. We thank you very much for coming to join us right on the eve of the Copenhagen conference.

JAMES HANSEN: Thank you for listening. Thanks.